What started with an experiment of living without looking at social media turned into quitting it completely, changing my reading habits, and stopping consuming news daily.

As the new step of decluttering my life, I am changing my approach to using services that heavily leverage algorithms to recommend new content, such as Netflix, Disney+, Apple TV, Prime Video, YouTube, Amazon, Letterboxd, LinkedIn, and more. I keep my accounts on most services, but intend never to scroll the feed or jump from one piece of content to another.

My goal is to stop relying on algorithmic feeds to fill my time. Many people find these algorithms helpful, but I find them detrimental.

The Why

Not only do I waste a lot of time, but I am also not even aware of wasting it. Companies using algorithmic feeds aim to obtain my time to the fullest without me noticing it. They create a frictionless user experience, which in turn allows them to serve better targeted ads (or sell more subscriptions). This doesn’t make any of these companies evil; it’s how business works.

My goals and these companies’ goals conflict. What matters to them does not matter to me. Although most products use algorithms (and prediction models) to engage me with what I may like, it almost always feels like a toxic relationship. Sex is good, but life would be much better without all the manipulation.

I wanted to get rid of manipulation and keep the good parts.

What to do

I set out for myself a single goal: Never look at any screen if I don’t already know what I’m looking for.

This goal is a fundamental shift in how I approach anything (adding another decision here). If I don’t know whether I really need a new shirt, I don’t buy one. If I don’t know which movie I want to watch, I either don’t watch one or first decide on the movie before turning on the TV. Deciding first before looking at any digital service forced me to build up an inventory.

Although I’m still crawling on this topic, I began keeping an inventory of movies to watch, things to buy, books to read, questions to find answers to, articles to write, people to get in touch with, restaurants to try, food to cook, and many more. These are plain lists that live in a note on my Obsidian (except articles and newsletters to read, which are on Readwise Reader; I’ll share more about it in another post) instead of other digital services.

I tried and used various other apps to manage all these lists. Oku for my books, Letterboxd for movies and TV series, Amazon for shopping list, and more. They were all convenient as I didn’t have to type in so many details—with one search and a click, the item is added to a list. Yet, convenience doesn’t make everything better.

Having a plain list in a file (or even on paper) has certain advantages. The friction of manual writing is itself a selection process. While adding an item, you have to write the full name and any details you need. You have no autocomplete, no suggestions. Before writing these, I consider whether I really want to write them down. Despite a bit of friction, it’s still easy; once you write the name in the inventory, it’s done. Choosing something from the inventory, on the other hand, is where I replace algorithms.

Compared to any of the products (like Amazon or YouTube), the information in the list is minimal. Look at your shopping list on Amazon; you have price, reviews, shipping information, and more. When you keep your own list, you have as much as your own entry. The trick is using the list as an initial decision point. When I want to watch something, I don’t go to Netflix or Apple TV directly; I open my list first, choose one, and search for it specifically. This approach breaks the association of “being bored” with any digital service. I intend to do a specific thing and avoid filling a gap with algorithmic recommendations in my life whenever I get bored.

“People are drawn to the easy and to the easiest side of the easy, but it is clear that we must hold ourselves to the difficult.” — Rainer Maria Rilke

However, this was not easy (and still isn’t). I needed to break some habits.

I constantly checked my phone for LinkedIn to see if I had a comment on my last post, or opened a YouTube video without thinking about it. After I come home from work, I feel tired and the phone is “just there” to fill the evening and “relax.” So, I looked for what I could do to change how I use my phone.

The How

After researching a lot, trying various methods, I established two guidelines for myself:

- No native apps on the phone; only the mobile browser will be used.

- Use tools to break unwanted habits.

No native apps

I already tried this approach when I was experimenting with living without social media. I knew it worked, but I needed a few changes.

Native apps are the grand palaces of companies. Companies customize everything inside to their needs (ideally, users’ needs, but not always). Giving these native apps real estate on my phone, the device that I carry with me everywhere, and putting them in a very accessible position makes it easier to use them. I want the other way around. Reaching these services should be really difficult; I must put in an effort. There has to be a lot of friction.

Hence, no native apps on the phone. That’s the rule. This way, I have to log in on a mobile browser, which doesn’t have the optimal user experience (because most products don’t care too much about mobile browser experience). Yet, this alone is not enough.

The mobile browser is still within reach. Adding only a second delay, sadly, doesn’t cut the habit. One recommendation I read somewhere (probably from James Clear or Cal Newport) told me to log in and log out of these services every single time, which I did. I even added two-factor authentication. But it still didn’t work well for me.

So, I had to add the second guideline.

Use tools to break unwanted habits

I get frustrated with bad user experience (UX) design and stop using the product. The problem is that most of the products I mentioned have great UX design. They create a seamless experience. They optimize algorithms to show you the next relevant thing in the most convenient way.

For example, I don’t want to scroll my YouTube feed because recommendations are still tailored to what I searched and watched (only lately, YouTube started introducing new topics to me). One thing I want to use YouTube for is to help my life. Yet, every time I open YouTube, I find myself checking other videos. YouTube makes it compelling to watch more with features like autoplay. So, I needed to break the UX.

There is a browser extension app called UnTrap for YouTube that works on iPhone Safari. It enables you to remove almost any feature YouTube has, ranging from removing the main feed to gray-scaling the whole website or removing buttons. After setting up the app and adjusting the design, here is a screenshot of what my YouTube looks like:

I removed the features I didn’t want to use. Decluttered my YouTube and left what I use: search and my profile page to access my history.

I needed something similar for LinkedIn. Again, luckily, there was another browser extension app from the same developer: SocialFocus: Hide Distractions. If you’re using any social media (ranging from Facebook to HackerNews), you can customize almost everything for the browser. I only use its LinkedIn features as I don’t use other websites.

Here is a screenshot of what my LinkedIn looks like now:

(Once a week, I check my feed, but do it on my laptop)

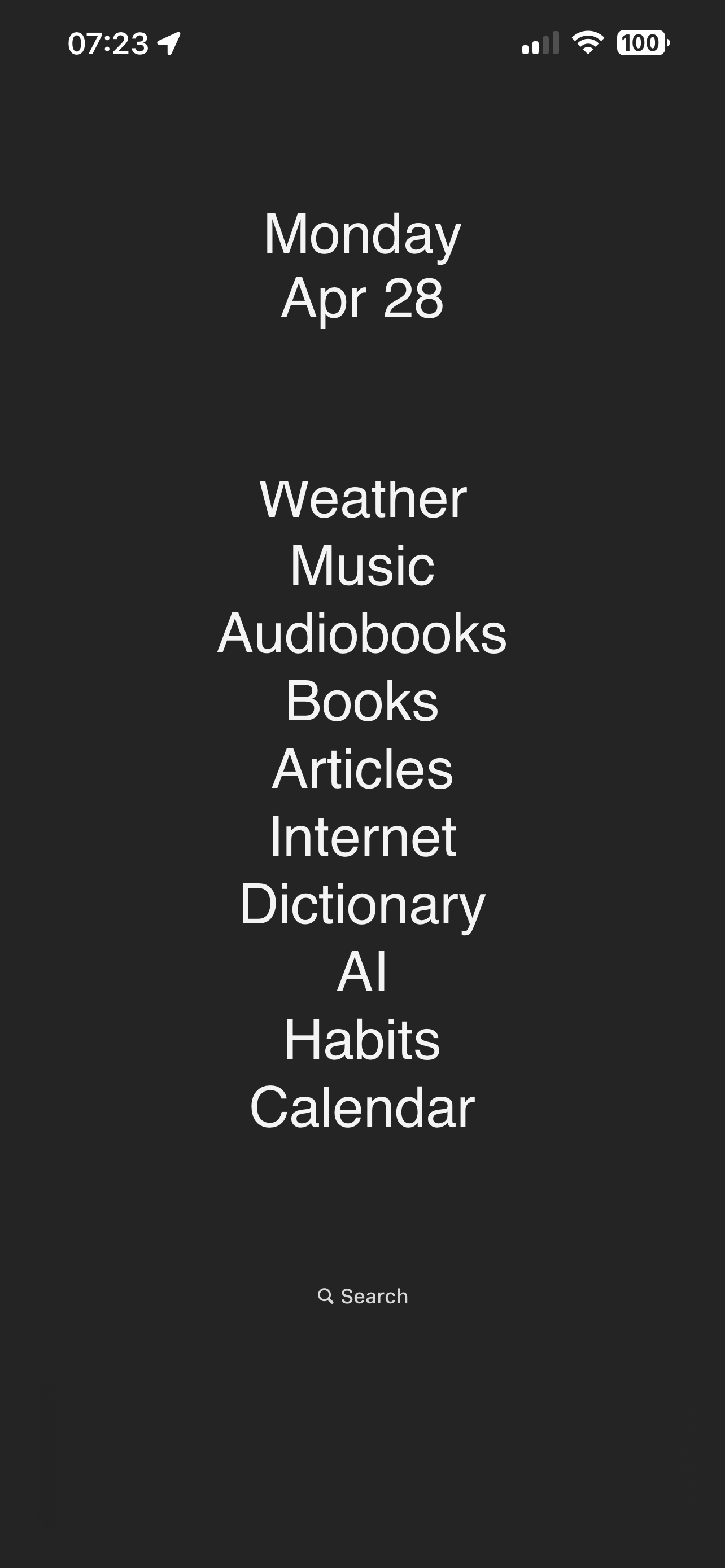

Last but not least, I needed to declutter my home screen on the phone. I first tried having an empty home screen. However, the iPhone’s library quickly replaced it while I was trying to access a few apps I used for different purposes. Most products leverage visual associations (like app icons) to remind me that the app exists and reinforce my habits of using the product more. I wanted to break these associations as well. I found an app call Blank Spaces to use my home screen without any app icons.

Here is a screenshot of my home screen:

I also turned off all Siri suggestions on my iPhone search (where you pull down the screen to search something).

The second guideline builds on top of the first guideline. By combining the two, I finally began seeing the impact and changes in my life. I pick up my phone less and less. I am able to evaluate and understand what matters to me the most. All the noise is gone.

Yet, every decision is a loss. What matters is understanding the gains as well as the losses of any decision.

Where I lose

Similar to my social media decision, the social impact of this decision is high. Cutting the ties with algorithmic feeds means I’m no longer informed about popular topics. In conversations with friends, I can’t contribute to discussions when they talk about a new TV series or movie or any other popular culture topic.

When I tell this to people, they are sometimes confused about whether I become aware of any topic at all. I do get to know them, but I do so either way later than the majority of social media users or from other sources.

Let’s take any popular Netflix show. Everyone learns about the show due to Netflix pushing it to the front row in the app. Some people immediately watch and form an opinion. In its first weeks, everyone talks about it (great marketing success, Netflix 👏🏼). I get to know there is a new show and whether it’s a good one via the people I know whose taste in shows is closer to mine. Then I add the show to my watchlist on Obsidian. When I want to watch something next time, I look at my list. By then, the hype is often gone and I can reason to watch it by sheer will, not popularity.

This approach may not apply to cinephiles or others with a passion. I don’t have a strong passion for the most popular subjects. I enjoy learning about many things, but can’t consider myself deeply knowledgeable in a single topic (I’m a multi-potentialite). I enjoy a lot of topics, but not so deep that I become a geek about it.

I constantly look for new topics and say no to many. Any algorithmic feed is where I cut things out. I find popular and hype culture via algorithms to be detrimental. I still learn many of the popular stuff via my friends, family, or the people I follow via RSS or email. But these almost always come too late, usually after the popularity is over. That means FOMO for many, but JOMO for me.

Last Thoughts

People underestimate real-life media. Before social media was defined with Facebook and Twitter, word of mouth was how society operated, and it still does today. People are under the illusion that popularity on platforms is everything. However, we still talk about what we are interested in and what’s popular in real life. The only difference is that you have to listen to people instead of seeing what they say from a screen.

Additionally, things-everyone-who-uses-social-media-knows are overrated. When you don’t have any algorithms that feed you with these popular topics like funny videos, you can send to your friend via Instagram DM (and receive a ❤️ emoji reaction), you do it in real life! All my friends talk about what they enjoyed or liked or found funny and show them to me. Real-life socialization is not extinct yet. It’s the actual way of being social (both for extroverts and introverts).

By choosing not to use algorithmic feeds, I rely on the word-of-mouth recommendation engine. I don’t care about how many people have seen a video on the other side of the world. I instead invest my energy in being part of a community, either around me or around a particular topic. When you look closely, it’s what everyone wants. The key to getting it is spending time on what matters to you, not what’s popular.

The popularity these days is in the hands of a few products. As their goals are focused on maximizing their profits, I don’t see a reason why I should keep using their recommendation engines. I prefer making my own feed in my own way.

Preview: